What Can You Draw to Represent Romeo and Juliet

Equally we are unsure of the date of William Shakespeare's birthday, it is traditionally historic around 23rd Apr, ironically the date of his expiry. This falls in springtime when, according to the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson 'a fellow's fancy lightly turns to thoughts of dearest.'

This year, in particular, the lovelorn have endured long periods of separation while they await to be reunited. By contrast, in Shakespeare's tragedy Romeo and Juliet, the headstrong young lovers reject to accept the separation caused by their warring families, and are impelled along a path which ultimately leads to their deaths.

The play has inspired fine art in all forms, from the musical West Side Story to Dire Straits' classic hit Romeo and Juliet, and Malorie Blackman's novel Noughts and Crosses. As the success of the recent pic of Romeo and Juliet from the National Theatre in London demonstrates, the story of the 'star-cross'd lovers' retains its powerful influence today.

Here we look at what artists on Art UK take fabricated of this timeless tale.

While some artists have been drawn to the tragedy of the story, in the nineteenth century artists were swept away by the romance. Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893) shared the aims of the Pre-Raphaelite painters who rejected the rapid industrialisation of their globe and revered the early Renaissance ideal of beauty.

Spurning the conventions of academy art instruction they used vivid colour to gloat the historic past, glorifying nature and placing an emphasis on emotion and subjectivity which reflected the concurrent Romantic movement in literature and art. The Pre-Raphaelites created a list of 'Immortals' and placed Shakespeare among them.

In this painting of the scene following the dark that the young newlyweds take only spent together in secret, Romeo, burial a last kiss in Juliet's neck, gestures urgently with his left manus to show her that he must leave earlier they are discovered by her mother Lady Capulet. Madox Brown conveys the passion and distress of the moment in the lovers' intertwined bodies. The billowing rich silks of Romeo'due south red costume advise the fire of his beloved, while Juliet glows like an icon in gold. The creative person meticulously details the apple tree blossom growing just below, alluding to Romeo'south earlier remark that 'this bud of dear, by summer's ripening / May prove a beauteous flower when adjacent we run into'.

Voted as Britain'south most romantic artwork in a contempo poll, Frank Bernard Dicksee's painting of the same scene reflects a growing trend for sentimentality in Victorian painting. This piece of work is based on an analogy he created in the 1880s for a luxury edition of Romeo and Juliet and embodies Romeo's line 'Farewell, farewell, one osculation and I'll descend'.

His detailed depiction shows the balustrade from inside, with the gilded light of dawn, the sign that Romeo must leave, illuminating the outer arch which frames the city of Verona in the distance. The couple are framed symbolically on one side by a passionfruit climber, its flowers in total bloom, and on the other by a bunch of white lilies that seems to foretell their deaths. Dicksee drew heavily on history and fable in his work and was influenced by the chivalric subject affair and intense colours used by the Pre-Raphaelites.

Whilst the Romeo and Juliet of Victorian paintings are portrayed equally real people whose tragic circumstances are designed to evoke our sympathies, there is a long tradition of art that captures the theatrical productions. No one did more than to revive Shakespearean theatre in the eighteenth century than the influential playwright, producer and player David Garrick. Garrick revolutionised theatre by doing abroad with the previously formulaic declamatory style of acting and introducing a much more naturalistic style of performance. He played numerous Shakespearean roles and managed the Drury Lane Theatre for 29 years, bringing Shakespeare to mass audiences and reviving many Restoration dramas.

This 1753 painting of the tomb scene is 1 of three versions past Benjamin Wilson on Art UK and represents Garrick's actual staging, with the Capulet tomb set towards the back of the stage. This enormously popular work spawned many engravings and other iterations such as box lids and enamel plaques. Garrick as Romeo stands in a feature pose of recoil, seen in other artworks, as he witnesses Juliet come back to life just after he has taken a lethal poison.

To mod audiences, it may look odd to see the lovers both nevertheless live when Shakespeare's text has Juliet waking merely after Romeo has perished, simply Garrick reworked the scene to permit the lovers the chance to say their farewells, a tradition that endured well into the nineteenth century. In a notorious theatrical boxing of 1750, competing productions of the play were mounted at the Drury Lane and Covent Garden theatres with Garrick'southward Juliet, played by the actress George Anne Bellamy, gaining the best notices. It may be this production shown here.

Retaining the Garrick interpretation simply in a distinctly dissimilar version of the tomb scene, here nosotros see the lovers in their last moments with the overturned cup of poison lying at their anxiety. Information technology was not unusual for actors in the eighteenth century to wear gimmicky courtly dress in their roles, something which may look strangely anachronistic to the modern center, only which bears comparison with a production today featuring the lovers in t-shirts and jeans.

This Juliet, Anne Brunton, came from a theatrical family – her father managed the Theatre Royal, Norwich. After she moved to Philadelphia in 1796 with her first married man Robert Merry she played Juliet again at the Chestnut Street Theatre. Joseph Holman is known to take played Romeo in 1784 at the Covent Garden Theatre, a production that may have inspired this work. He also moved to Philadelphia, where he managed the Walnut Street Theatre.

In Joseph Wright of Derby's searing revelation of the tragic terminal scene, Juliet, weeping over her expressionless lover, is disturbed by an budgeted baby-sit whose shadow we run across in the doorway. Wright employs his mastery of light to illuminate her equally a awe-inspiring figure in the moment earlier she uses a dagger to join her husband in decease.

This painting was among many made for the Shakespeare Gallery initiated in 1876 past engraver and publisher John Boydell. Artists such as Joshua Reynolds, Robert Smirke, James Northcote and John Francis Rigaud were commissioned to create artworks for the gallery, but when Wright discovered that he had been consigned to a secondary and less well-paid class of painters he consequently had a row with Boydell which resulted in this painting being rejected.

More than often than not it is indeed Juliet rather than Romeo who is the focus of the artist. Sally (Sarah) Booth, seen here, opened the 1827 season at the Georgian Playhouse Wisbech (now the Angles Theatre) as Juliet. Described as 'small in stature, nervous, with hair inclining to red' she was often bandage in juvenile roles. At this moment, having been matrimonial against her will to Paris (and already secretly married to Romeo) Juliet stands in her bed-chamber under an ominous moon, contemplating the herbal draught that volition put her into a semblance of sleep.

1 of the twentieth-century theatre's most renowned Juliets, Peggy Ashcroft played the part for the second time in 1935 under John Gielgud's direction, with Edith Evans as the Nurse, earning glowing reviews. The function of Romeo was taken on alternate nights past Gielgud and Laurence Olivier. Ethel Léontine Gabain was known for her oil portraits of actresses in character and was particularly drawn to depictions of women in a state of melancholy. She gained a prestigious reputation for her lithographs and was elected President of the Society of Women Artists in 1940.

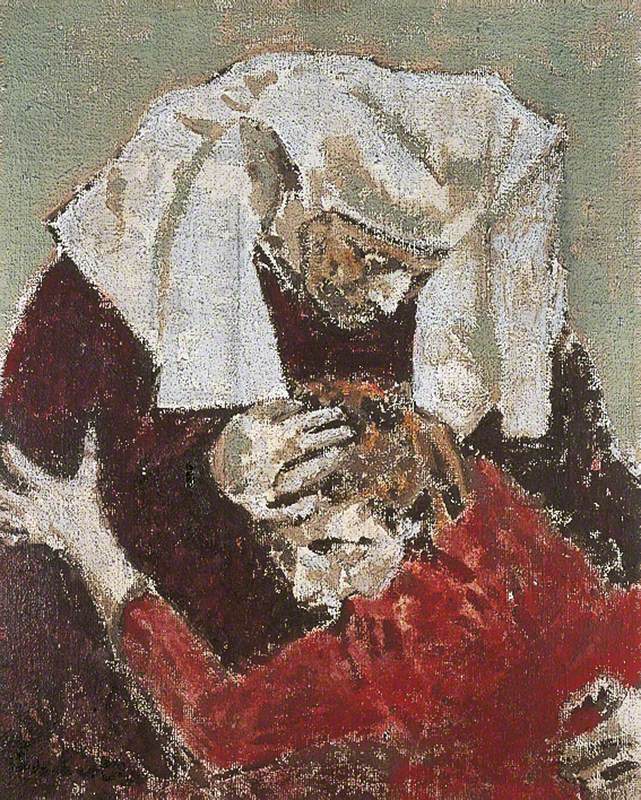

The same theatre product features in Walter Richard Sickert's moving depiction of Juliet with her nurse. A frequent theatregoer, Sickert fabricated many friends among actors and painted Peggy Ashcroft and Edith Evans several times. His technique of flat dry-scraped paintwork, seen here, often left bare patches of canvas visible and allowed for expansive flat patches of tonal colour. The graphic style owes something to Sickert'south method at this fourth dimension of painting from printing images and embodies the elementary heartache of a young girl in the throes of love, cartoon comfort from the one person she can trust.

In this tiny oil painting (16.1 x 26.9 cm), perchance a written report for a larger work, John Everett Millais marks the 'fearful passage' of Romeo and Juliet's 'decease-mark'd love' with a tableau of the final scene where the Montague and Capulet families agree to be reconciled. The intensity of colour and employ of natural calorie-free to illuminate the scene are typical of Pre-Raphaelite sensibility. By placing the bodies of the lovers in the centre he cuts the painting across the diagonal, reminding u.s. of the division between the families that will ultimately exist healed by the tragedy.

This story with its indelible theme of young love thwarted and doomed by prejudice and misunderstanding remains relevant for every age and volition continue to exist the spur to new interpretations.

Lucy Ellis, freelance author

More stories

Artworks

Source: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/star-crossed-lovers-romeo-and-juliet-in-art

Post a Comment for "What Can You Draw to Represent Romeo and Juliet"